This past weekend I took my first shot at riding the Great Allegheny Passage. I’ve been reading about this for years, but until now I haven’t had the endurance or bike repair skills to tackle any of the longer segments.

The GAP is part of a 342-mile trail stretching from Pittsburgh PA to Washington DC. It follows abandoned rail lines including the Baltimore & Ohio and Western Maryland railroads and runs on a gentle 1% – 2% grade, usually over crushed limestone. Technically the GAP runs from Pittsburgh to Cumberland MD, and the C&O Canal Towpath runs from Cumberland to Washington DC. But who’s counting?

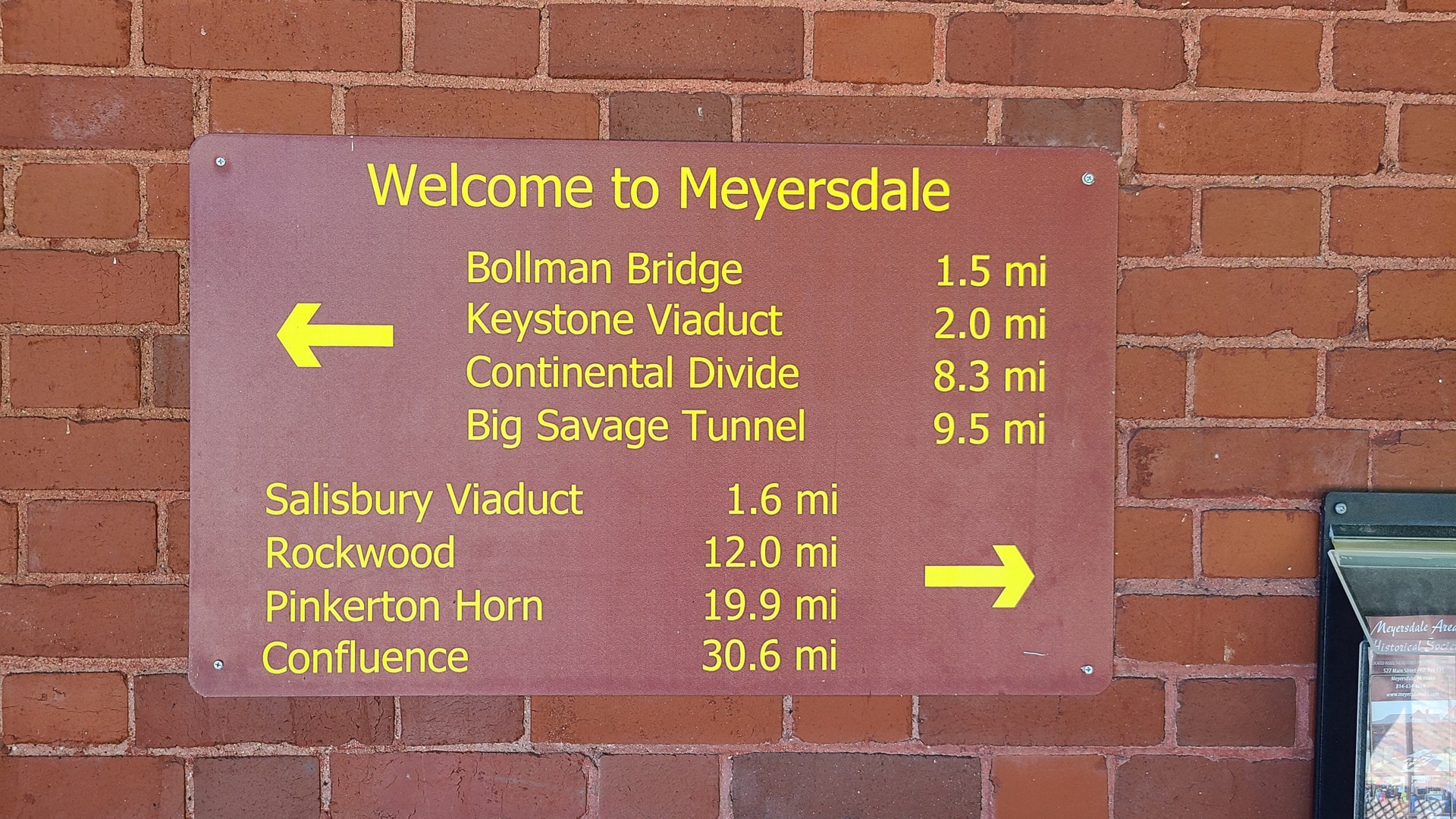

My journey started in Meyersdale (PA) at an old Western Maryland Railroad station — now home to the Meyersdale Area Historical Society. Built in 1911, the building’s last passenger service ran in 1936, and its final freight run was around 1975. The building sat neglected for 20 years until reopening as a museum in 1995.

The weather for my trip couldn’t have been better. High in the upper 80s, scattered clouds, and neither rain nor unyielding sunlight in sight. This segment of the trail is about a 50/50 split between exposure and shade. My wife dropped me off in Meyersdale at 2, then took off for the hotel in Cumberland.

Almost immediately after heading out I encountered the Bollman bridge. This is one of the few surviving iron railroad bridges in the country. It was previously slated for demolition but rescued, restored, and relocated to be part of the trail in 2006. What makes this bridge so special is not only that it was built out of iron (most surviving metal rail bridges are made of steel) but that it was built to be modular. Relatively unskilled laborers could quickly assemble it with little to no training.

Wendel Bollman — the original engineer of the bridge — was entirely self taught. Seems all the more remarkable that this bridge went from being Yet Another Forgettable Rail Bridge to a special part of the GAP.

The trail has no shortage of tunnels, bridges, and sweeping vistas. Some of the bridges are in better shape than others, but none lack character. If you need some photography inspiration and are up for a 30-something mile ride, this segment fits the bill! In cases like the bridge below, there’s always a newer walkway providing safe passage.

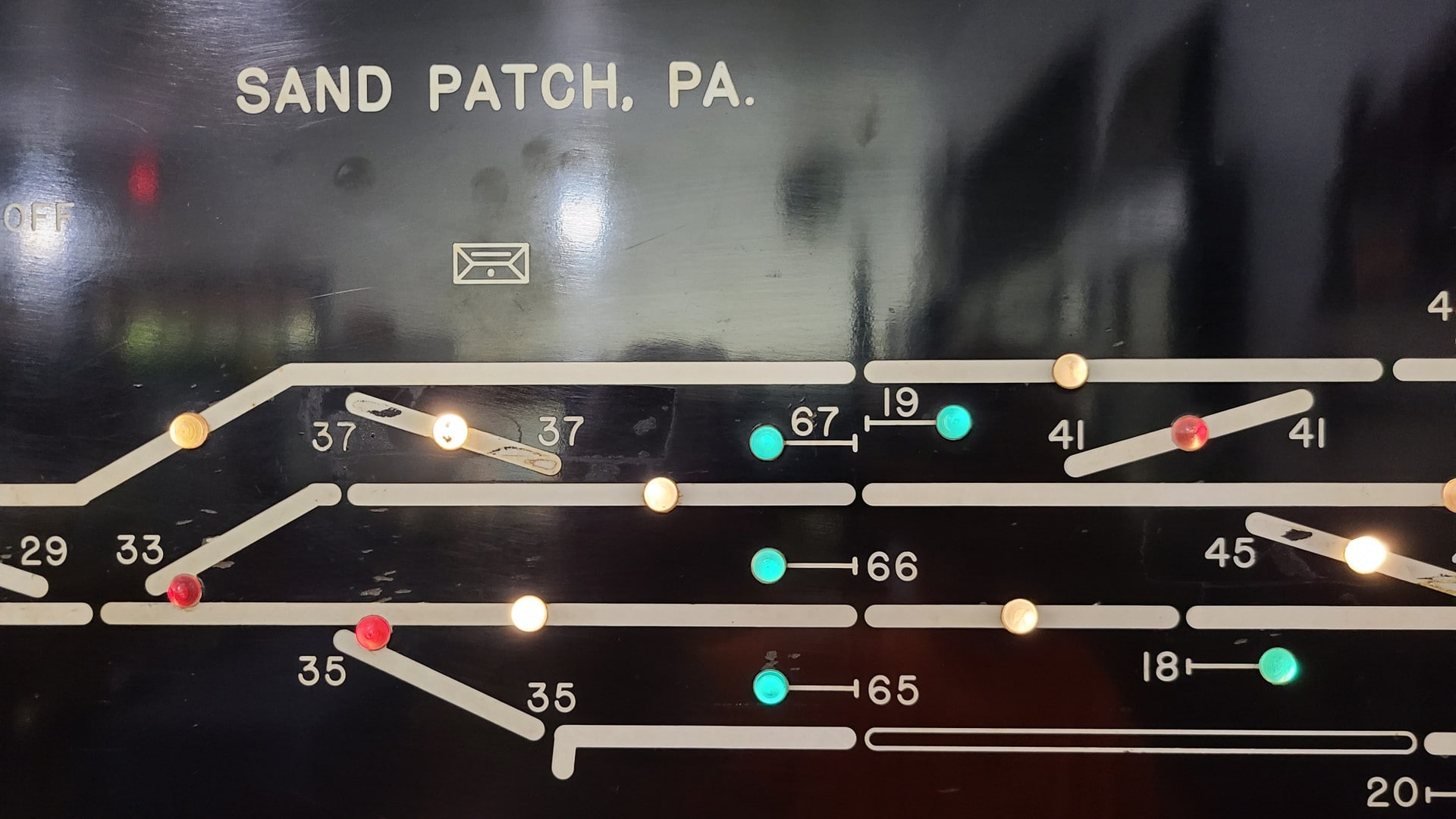

Big Savage Tunnel is one of the big attractions of this segment. Opened in 1912 for the Western Maryland Railroad and abandoned in 1975, it sat decaying for 30 years before being brought back to life for the Great Allegheny Passage.

The interior was so badly destroyed that workers originally encountered 20-foot-long icicles and literal tons of debris. Holes in the roof were large enough for adults to enter and move around comfortably. They never really found a good workaround for winter weather, so the tunnel doors are closed between November and April each year.

Today, thanks to an $11 million refurbishment, the tunnel is safe, well-lit, and mostly dry. Ride into the tunnel during the summer months, and the damp 55-degree air is like hitting a blast of all-natural 100% organic air conditioning.

Just past the tunnel is one of the best views on this segment. Benches, pavillions, restrooms, and bike fixit stations all line the trail here. The fixit station has a QR code that takes you to a guide to repairing just about anything on your bike. If you need a place to pause for a snack, this is as good a spot as any!

Just south of the Big Savage tunnel is the Mason Dixon line. The chain-like engravings represent the chains surveyors would use to map on state borders a few centuries before GPS came along. Each segment is a foot long, and the chain was 66 feet in length.

In addition to the tunnels and scenery, there are lots of spots along the trail where echoes of past industry or development can still be heard — if you know how to look. Take this bridge just north of Big Savage, for example:

That bridge is pretty unremarkable and you might be tempted to just ride over it without a second thought. But there IS something remarkable about it: it doesn’t go over anything. There isn’t any evidence of water nearby and the terrain is too unforgiving for a road or railbed. So what was it?

The first thing I did was pull this section up on a map. There’s a treeline pointing in the general direction of this bridge, and it happens to straddle the county border, but that’s about it. So I dug a little deeper and pulled up some historic aerial photos. In the 1940s I found a farm lane that connected Old Mt. Savage Road with Shirleys Hollow Road — and it passed underneath this bridge. You can very clearly see the path of the road on statewide LIDAR images. Judging by the age of the trees growing in the path of the road, along with subsequent historic photos, the road appears to have been abandoned in the late 50s or early 60s.

I wasn’t as lucky with some of the other ruins. The bridge below was over the line in Maryland, just past the range of my resources. The surrounding terrain shows clear evidence of a railroad having been here at one time. There’s also a small flat area further up the hill that today holds mining waste piles. My best guess is that this might have been a private rail line running from a nearby mine into Mount Savage, a small town about two miles to the east southeast.

The second tunnel I ran through was the Borden tunnel. Like Big Savage, it was built in 1911 and left to rot in 1975 when the Western Maryland Railway abandoned its Connellsville subdivision. A nearby solar panel provides power for the lighting, which is triggered by motion sensors. A neat idea but not well executed; the lights turn on as you pass them so they do a great job of lighting you up instead of the road.

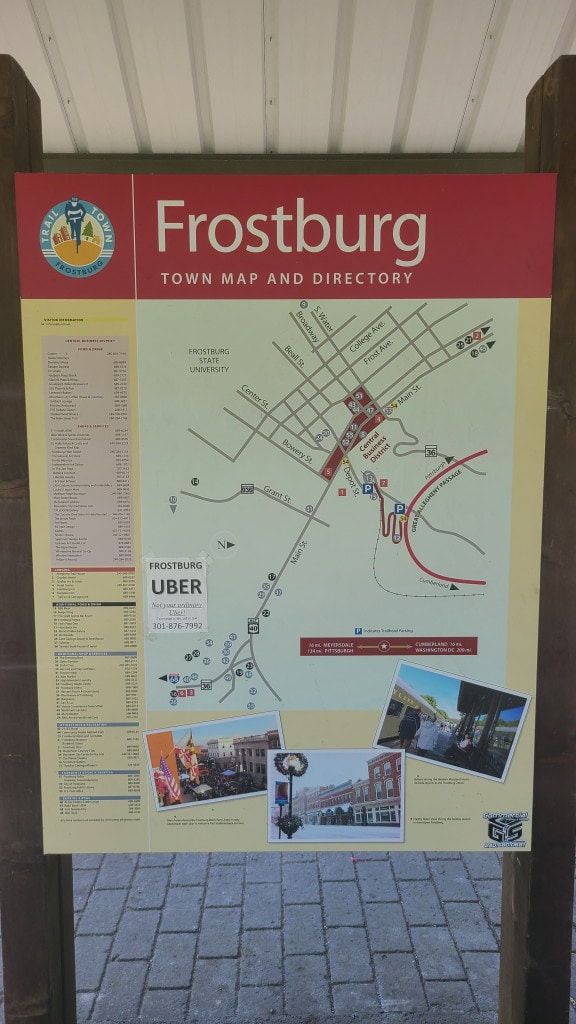

Frostburg has an interesting trailhead. A series of switchbacks leads up through an art garden and provides a barely-a-mile connection to downtown — and all of its bars, restaurants, and services. Navigating Frostburg is roughly equivalent to navigating Mt Everest. I didn’t go all the way into downtown but there’s a no-frills cafe at the top of the hill that was kind enough to let me grab a snack.

If you hit up any of the downtown pubs, don’t worry: the ride from Frostburg to Cumberland was a short, shady, leisurely jaunt downhill.

Brush Tunnel was the last tunnel before rolling into Cumberland. The Western Maryland Scenic Railroad runs through both this and the Borden tunnel. Highly recommended if you haven’t ridden it!

The final stretch into Cumberland begins to perk up with signs of civilization. It’s mostly industrial areas until you hit downtown, which is loaded with restaurants, pubs, cafes, and shops. There’s a well-equipped bike shop just past the railroad station if you need anything, and the city has ample bike racks and bike lockers. The several nearby hotels make this an idea overnight stop if you want to continue south towards DC.

Cumberland is where the Great Allegheny Passage officially comes to an end. The C&O Canal Towpath starts here and runs through Harpers Ferry onward to Washington DC. The two segments combined clock in at just over 333 miles — about ten separate segments for me. If you’re adventurous, campgrounds along the way provide plenty of opportunities for bikepacking. There are people who have done the entire trail in two or three days.

Maybe next year.